The Age of Enlightenment was an intellectual and philosophical movement that dominated the world of ideas in Europe during the 17th and 18th centuries. Philosophers and scientists of the period widely circulated their ideas through meetings at scientific academies, Masonic lodges, literary salons, coffeehouses, and in printed books, journals and pamphlets. The ideas of the Enlightenment undermined the authority of the Monarchy and the Catholic Church and paved the way for the political revolutions of the 18th and 19th centuries.

The “Radical Enlightenment” promoted the concept of separating church and state, an idea that is often credited to English philosopher John Locke (1632–1704). According to his principle of the social contract, the government lacked authority in the realm of individual conscience, as this was something rational people could not cede to the government for it or others to control. For Locke, this created a natural right in the liberty of conscience, which he said must therefore remain protected from any government authority.

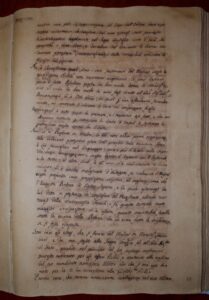

This letter was written exactly 229 years ago, on March 31, 1792 and is kept by the Cathedral Archives of Malta (L-Arkivji tal-Kattidral). The letter illustrates the ways in which Enlightenment ideas undermined the authority of the Catholic Church in Malta in the 18th century.

The author was the Inquisitor Giovanni Filippo Gallarati Scotti who wrote to Cardinal Francesco Saverio De Zeleda in Italian language. The object of his letter is Giovanni Nicolò Muscat, the Uditore or General Advocate to Grand Master De Rohan (1727–1795). Muscat was born in very poor circumstances in Valetta on March 8, 1735. However, he was brought up by his aunt, who paid his studies. Muscat was profoundly immersed in the culture of the Enlightenment.

He was a firm believer of Voltaire’s view that Enlightened Despotism was necessary to strengthen the power of sovereigns in all matters, to promote social well-being and political stability. During the Enlightenment in Malta as in Central Europe, such ideas favoured by Monarchs and the Grand Masters clashed with the authority of the Catholic Church; the bishops and inquisitors had their own tribunals, superior censoring rights and held the monopoly on education.

One of the fiercest battles was that over the exequatur or, as it was more commonly known in Malta, the Vidit. The Government claimed the right to sanction or prohibit the execution of any legal instrument issued by foreign courts. The auditor of Mgr. Scotti, the Inquisitor, argued with Muscat that this law was harmful to ecclesiastical liberty and to the privileges and dignity of the Pontifical Tribunals. Muscat maintained that the Church could exert its jurisdiction solely in matters pertaining to the Sacraments, the faith, morals, and ecclesiastical discipline, though He avowed to have been, was, and always will be, a true and faithful son of the Church.

In the letter, Giovanni Nicolò Muscat, is now said, as described by Inquisitor Scotti, to have publicly exclaimed “indecent expressions” including that the age of the power of the Church is over, thus affirming his belief that the power of Enlightened Sovereigns should replace that of the Church.

Gio’ Nicolo’ Muscat can certainly be described as a most outstanding and stupendous philosopher. He dared to challenge the hegemony of the Catholic Church in an age when it was right across-the-board.

This record will be showcased at the first thematic exhibition of the European Digital Treasures project, entitled Construction of Europe – History, Memory and Myth of Europeanness over 1000 years.

Anna Palcso, Public Education Officer at National Archives of Hungary