109 years ago, today, on 15 April 1912 at 2:20 am, after striking an iceberg during her maiden voyage from Southampton to New York City, RMS Titanic broke apart and sank south of Newfoundland, in the North Atlantic Ocean. With its 46,300 gross tons, RMS Titanic was the world’s largest passenger ship afloat at the time she entered service. It was thought that the huge ship with 16 watertight bulkheads simply could not sink. The disaster was met with worldwide shock and outrage at the huge loss of life, as well as the regulatory and operational failures that led to it.

Titanic´s passengers numbered approximately 1,339 people. It had around 885 crew members, of which only 23 were women. Only 710 survived out of a total of around 2,224 people onboard. The ship carried some of the wealthiest people in the world, as well as hundreds of emigrants from Great Britain, Ireland, Scandinavia and elsewhere throughout Europe. The first-class accommodation was designed to be the pinnacle of comfort and luxury, with a gymnasium, swimming pool, libraries, high-class restaurants, and opulent cabins.

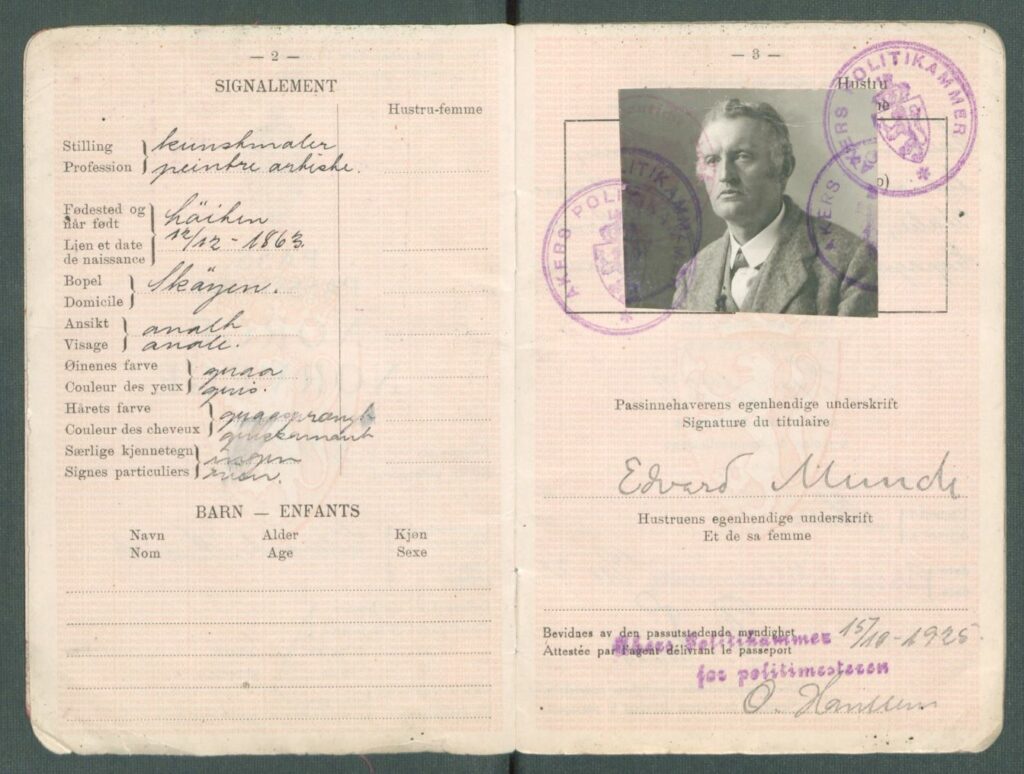

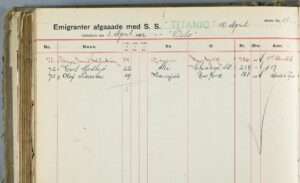

This document is held in the National Archives of Norway as part of the collection of the White Star Line shipping company. The White Star Line was British owned but had an office in Oslo for processing Norwegian passengers who wished to make a connection to the UK in order to secure passage on one of the vessels sailing for America. Recorded on the list are three of the 28 Norwegian passengers who sailed with the Titanic when she departed from Southampton on 10 April 1912. Two of those listed, Arne Johan Fahlstrøm and Carl Midtsjø, made the connecting trip from Christiania (later Kristiania, the old name for Oslo) on 3 April (their ship was named the ‘Oslo’). The third, Olaf Pedersen, eventually travelled from Larvik on 5 April. Of these three men, only Midtsjø survived the Titanic disaster.

The list of the three Norwegian passengers is part of the Archival Literacy Online Course, a European Digital Treasures project to assist teachers in introducing students of grade 9 and higher to the world of archives. It is included in Module 3 – Pandemic and Epidemics, Economic Crises and Migration.

The Norwegians on the Titanic also formed part of a wider historical story, that of the mass migration of many millions of Europeans to America. And it was first and foremost this emigration that made the traffic across the Atlantic Ocean profitable in the beginning of the 19th century. This movement of people had been ongoing since the ‘discovery’ of the New World in the late fifteenth century. However, by the mid-nineteenth century better connections and lower costs had helped facilitate the transportation of an ever-increasing number of individuals. Until World War I, around 100,000 persons from Northern Europe emigrated each year. A majority were attracted by the greater opportunities that expanding countries such as the USA could offer. In that sense they were motivated by what historians have referred to as ‘pull’ factors. But at certain points in time so-called ‘push’ factors came to predominate. During the late 1840s, for example, a large wave emigrated in desperation from Ireland and Germany following the onset of crop failure, famine and political unrest in their home country.

Midtsjø, Fahlstrøm and Pedersen had, each in their own way, all gone in search of opportunities available to them in America. Fahlstrøm had been gifted the price of passage by his parents so that he could study theatre in New York. Pedersen was already a citizen of the USA and was returning there after a sojourn back in Norway, where he had got married. The intention was that his new Norwegian wife would join him in America once he had made enough money to support a family. Midtsjø was the son of a farmer and was the first of several siblings who emigrated to the USA. Given that he travelled third class and was a healthy adult male he must have counted himself very lucky that he found a place on one of the Titanic’s lifeboats on that fateful night.

Biographies of the three Norwegian passengers

Arne Johan Fahlstrøm, who according to the passenger list travelled on first class on the transport ship from Oslo, is on Titanic’s passenger lists among those who travelled on second class. As a reward for a good exam, the parents gifted their 18-year-old son the price of passage to the United States where he should study film and theatre in New York. Both his parents were actors and had in 1897 established the Central Theatre in Oslo. They lost their only child and bequeathed their entire fortune to the Rescue Society to prevent new accidents at sea. A lifeboat came to bear the son’s name.

Carl Midtsjø travelled on Titanic’s third class. He was a farm boy from Ski outside Oslo and was the first of several siblings who emigrated to the USA. Carl was lucky and got a place in one of the lifeboats – no. 15 with passengers from all classes. In some of the lifeboats, there were in fact also blind passengers from the Titanic. In a letter to his brother shortly after the accident, he wrote that while people were desperately trying to save themselves on board the lifeboat, one of them was shot at. For Carl, life went on. On 4 August he turned 22 years old. He married the following month and remained in America for the rest of his life.

Olaf Pedersen came from Sandefjord, a small town an hour outside of Oslo, was 29 years old and travelled on third class. He was already a citizen of the USA and was returning there after a sojourn back to Norway where he had got married on 17 March. Now he wanted to cross the Atlantic again to earn money for his new family. It was intended that his Norwegian wife should follow later. Less than a month after the wedding, she became a widow instead. She made a living by sewing and never remarried.

Further reading:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Titanic#Survivors_and_victims

https://www.encyclopedia-titanica.org/